Samuel Pepys was born just inside the western edge of City of London to a tailor and the daughter of butcher in 1633 in the parish of St Brides. Through the benefaction of his mother’s family he was sent to Cambridge University and further still through these connections and his relative the Earl of Sanwich, Edward Montagu, he carved himself out a niche in the Royal Navy office.

Pepys lived in a time great social upheaval, revolution, innovation and tragedy.

On the continent of Europe more than 4.5 million people died as a result of the Thirty Years War between 1618 and 1648. In Ireland, tens of thousands of protestants were murdered in the Catholic uprising of 1641 and a decade later Oliver Cromwell would unleash brutality similar to that found in the worst of extremes of the wars of continental Europe upon the same Irish catholic population.

Public executions were common with more than twenty three happening just metres from St Olave’s on Tower Hill in Pepys’ lifetime. He would have seen the heads of recently executed criminals publically displayed upon spikes when entering London from the southern side of London Bridge until 1660.

Pepys was a passionate bibliophile and had a voracious appetite for the pleasure of discovering new culture and the arts especially theatre and music. He was instrumental in the development of the Royal Navy eventually having oversight of the biggest single employer in England. He served as a Member of Parliament and had close associations with influential historical figures from Charles II to Sir Isaac Newton to name just a couple.

His life during an era where the monarchy was first abolished through an act of regicide upon Charles I in 1649 and then renewed with the restoration of Charles II in 1660 was at a time of supreme historical significance in the constitutional history of England and the British Isles. Indeed, Pepys recalls in his diaries the executions of selected regicides and was part of a party sent to accompany the king on his voyage back from exile on the continent in 1660.

He would have seen many personal, economic and cultural freedoms were suppressed violently by an extremist puritan state during the 1650s. Between 1660 and 1669 he maintained a secret diary written in short hand in which he recorded with remarkably candid detail his thoughts, experiences and observations of the times in which he lived.

These were written against a backdrop of considerable catastrophy in London with the Great Plague of 1665 and the Great Fire of 1666 following a period of moral austerity of exceptional intensity and perhaps the bloodiest war ever fought on English soil.

This was not without risk within the context in his era. Indeed, owing to his service to Charles II and more closely to the Duke of York, the future James II; Pepys would find himself imprisoned in the Tower of London in the 1680s under suspicion of being a secret Catholic.

Perhaps what has made his diaries since their publication in the 19th century so enduring in their popularity and usefulness to scholars and the historically curious alike is the breadth and scope of his observations.

It is principally thanks to Pepys that much of our understanding of life during the period and several key events in the nation’s history can be found.

Beyond this, they serve as a candid portrait characterised not least by his reflections upon his own moral failings, indulgences and passions.

These are perhaps as much acts of confession as they are celebratory reflections of pride in the growth of his wealth and status.

The most apparent example of this can perhaps be found at St Olave’s with the monument to his wife Elizabeth who died in 1669 just six months after he concluded his diaries, where she looks down in constant gaze upon where Pepys would have continued to sit in church. The position of this monument and the knowledge that Pepys did not remarry, suggests a desire to atone for his past acts of adultery and to subject himself to her enduring judgment upon his behaviour in the remainder of his days.

His diaries serve as a lucid portrait of humanity with all of its failings at a time when moral codes, social customs and conventions were in some ways as different to our times today.

In Pepys’s account of his experiences, he has left us with some intriguing references to the day to day life and social interactions between the parishoners of St Olave’s; we have compiled just few extracts from his diaries below relating to his thoughts including two whom also have memorials in the church, as well as a number of references to his relationship with Daniel Milles its then rector.

Our commemoration of Pepys at St Olave’s acknowledges cultural significances, virtues and moral weaknesses. We encourage those curious to explore his diaries and are happy to share some resources that may aid you in your discovery; we also welcome all who wish to visit the church of St Olave’s Hart Street to do so and explore this story first hand.

A searchable database of his diaries.

A society dedicated to exploring Pepys’s history and cultural legacy.

Samuel Pepys & The Great Fire Of London (Podcast)

A podcast exploring the Great Fire of London through Pepys’s diary.

DIary Extracts

Pepys & The Parish

Parishoners

Sir Andrew Rickard

“So made myself ready and to church, where Sir W. Pen showed me the young lady which young Dawes, that sits in the new corner-pew in the church, hath stole away from Sir Andrew Rickard, her guardian, worth 1000l. per annum present, good land, and some money, and a very well-bred and handsome lady: he, I doubt, but a simple fellow. However, he got this good luck to get her, which methinks I could envy him with all my heart. “

3rd May 1663

Parishoners

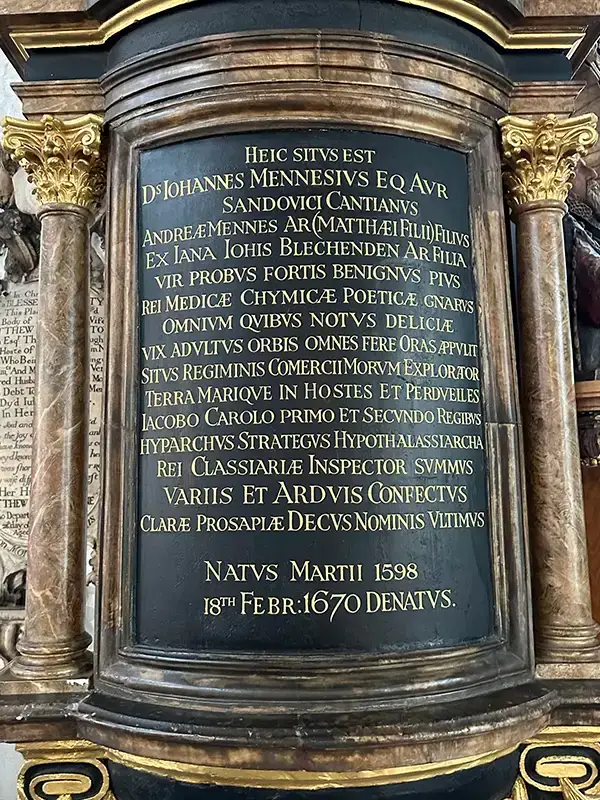

Sir John Mennes

“Sir J. Minnes was in the highest pitch of mirthe, and his mimicall tricks, that ever I saw, and most excellent pleasant company he is, and the best mimique that ever I saw, and certainly would have made an excellent actor, and now would be an excellent teacher of actors. ”

2nd January 1666

“I to Captain Cocke’s, where I find my Lord Bruncker and his mistress, and Sir J. Minnes. Where we supped (there was also Sir W. Doyly and Mr. Evelyn); but the receipt of this newes did put us all into such an extacy of joy, that it inspired into Sir J. Minnes and Mr. Evelyn such a spirit of mirth, that in all my life I never met with so merry a two hours as our company this night was. Among other humours, Mr. Evelyn’s repeating of some verses made up of nothing but the various acceptations of may and can, and doing it so aptly upon occasion of something of that nature, and so fast, did make us all die almost with laughing, and did so stop the mouth of Sir J. Minnes in the middle of all his mirth (and in a thing agreeing with his own manner of genius), that I never saw any man so out-done in all my life; and Sir J. Minnes’s mirth too to see himself out-done, was the crown of all our mirth… it being one of the times of my life wherein I was the fullest of true sense of joy.”

10th September 1665

Pepys & The Priest

Reverend Daniel Mills

“(Lord’s day). In the morn to our own church, where Mr. Mills did begin to nibble at the Common Prayer, by saying “Glory be to the Father, &c.” after he had read the two psalms; but the people had been so little used to it, that they could not tell what to answer. This declaration of the King’s do give the Presbyterians some satisfaction, and a pretence to read the Common Prayer, which they would not do before because of their former preaching against it.”

November 4th 1660

“(Lord’s day). At church in the morning, and dined at home alone with my wife very comfortably, and so again to church with her, and had a very good and pungent sermon of Mr. Mills, discoursing the necessity of restitution.”

25th August 1661

“Lord’s day). Up pretty well in the morning, and then to church, where a dull doctor, a stranger, made a dull sermon.”

6th January 1666

“Up, and being ready, walked up and down to Cree Church, to see it how it is; but I find no alteration there, as they say there was, for my Lord Mayor and Aldermen to come to sermon, as they do every Sunday, as they did formerly to Paul’s. Walk back home and to our own church, where a dull sermon and our church empty of the best sort of people, they being at their country houses, and so home, and there dined with me Mr. Turner and his daughter Betty.”

August 18th 1667

“(Lord’s day). Up to my chamber, there to set some papers to rights. By and by to church, where I stood, in continual fear of Mrs. Markham’s coming to church, and offering to come into our pew, to prevent which, soon as ever I heard the great door open, I did step back, and clap my breech to our pew-door, that she might be forced to shove me to come in; but as God would have it, she did not come. Mr. Mills preached, and after sermon, by invitation, he and his wife come to dine with me, which is the first time they have been in my house; I think, these five years, I thinking it not amiss, because of their acquaintance in our country, to shew them some respect. Mr. Turner and his wife, and their son the Captain, dined with me, and I had a very good dinner for them, and very merry, and after dinner, he [Mr. Mills] was forced to go, though it rained, to Stepney, to preach. We also to church, and then home,”

Sunday 15th September 1667

“back to the Old Exchange, and there at my goldsmith’s bought a basin for my wife to give the Parson’s child, to which the other day she was godmother. It cost me; 10l. 14s. besides graving, which I do with the cypher of the name, Daniel Mills”

“at noon home, where my wife not very well, but is to go to Mr. Mills’s child’s christening, where she is godmother, Sir J. Minnes and Sir R. Brookes her companions.”

21st November 1667

“(Lord’s day). Up, and after entering my journal for 2 or 3 days, I to church, where Mr. Mills, a dull sermon: and in our pew there sat a great lady, which I afterwards understood to be my Lady Carlisle, that made her husband a cuckold in Scotland, a very fine woman indeed in person. “

Sunday 1st December

“1667 in the evening comes Mr. Mills and his wife and supped and talked with me, and so to bed. This last night Betty Michell about midnight cries out, and my wife goes to her, and she brings forth a girl, and this afternoon the child is christened, and my wife godmother again to a Betty.”

12th July 1668

As we commemorate Samuel Pepys at St Olave’s, we need to acknowledge that he profited from shares in the Royal Adventurers into Africa, who at that time had a monopoly on the slave trade. Pepys would have profited from the slave trade through his business investments.

His diaries may also reveal the ill treatment Africans suffered. On 7 September 1665 Pepys notes in his diary that the banker Sir Robert Vyner, showed him ‘a black boy that he had that had died of consumption’. Vyner had then dried the body in an oven and placed in a box to be displayed to his visitors.

However, the term ‘black boy’ was also commonly used to describe one with dark hair or features most broadly associated with Charles II (known as the ‘black boy’). Pepys’s world was at least if not more so a society divided by religion than necessarily one divided by race.

In other instances we know of Pepys joking with and enjoying the company of black africans such as Mingo who was a man servant of Sir William Batten.

On Valentine’s Day in 1661, Pepys recorded an encounter with Mingo, “up early and to Sir W. Batten’s, but would not go in till I asked whether they that opened the door was a man or a woman, and Mingo, who was there, answered a woman, which, with his tone, made me laugh.”

Upon the death of Sir William Batten in 1667, Mingo would inherit an allowance of £20 per year and Batten’s rights to operate a light house in Harwich, which would see him leave London to become a successful lighthouse keeper.

On Friday 8th 1661, Pepys recounts a drinking session in the Fleece Tavern with a group of sailors including two former slaves:

“telling stories of Algiers, and the manner of the life of slaves there! And truly Captn. Mootham and Mr. Dawes (who have been both slaves there) did make me fully acquainted with their condition there: as, how they eat nothing but bread and water. At their redemption they pay so much for the water they drink at the public fountaynes, during their being slaves. How they are beat upon the soles of their feet and bellies at the liberty of their padron. How they are all, at night, called into their master’s Bagnard; and there they lie. How the poorest men do use their slaves best. How some rogues do live well, if they do invent to bring their masters in so much a week by their industry or theft; and then they are put to no other work at all. And theft there is counted no great crime at all.”