St Olave's Hart Street

Our Story

From the Battle of London Bridge to the diaries of Samuel Pepys, through wars and rehallowing; discover the fascinating stories that have made a very special sanctuary.

From the Battle of London Bridge to the diaries of Samuel Pepys, through wars and rehallowing; discover the fascinating stories that have made a very special sanctuary.

St Olave Hart Street is one of the few mediaeval churches to survive the Great Fire of London. It is best known as the burial place of Samuel Pepys and his wife Elizabeth; the famous diaries of Samuel Pepys provide the most vivid first-hand account of the fire of 1666 and subsequent life.

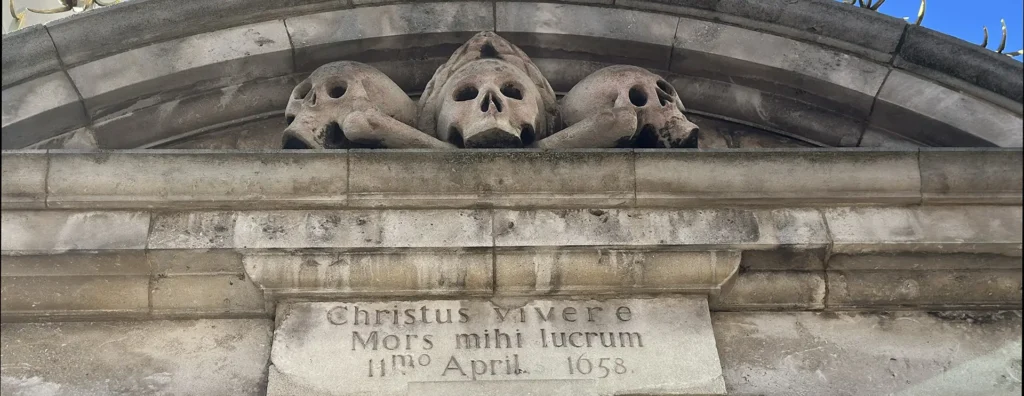

St Olave’s has strong links to several historic London livery companies and other historic associations, most notably The Clothworkers’ Company, The Trinity House, The Environmental Cleaners and The Pepys’ Club. The Victorian author Charles Dickens lived close by and called St Olave’s ‘St Ghastly Grim‘, referring to the gargoyles on the churchyard gate.

St Olave’s has been a place of Christian worship and sanctuary for almost 1000 years.

The church is named after Saint Olave. At the 1014 Battle of London Bridge between the Danish army and the English King Ethelred, known to history as ‘The Unready’; Olav supported the Christian king of England in an attempt to regain his throne from the pagan Danes. In Rouen, Olav encountered the faith of Jesus Christ and was baptised in Rouen, France.

The first church in Hart Street may have been erected around AD 1050, a simple timber structure and in the 13th century, it was rebuilt in stone, and then again in 1450 under the patronage of Richard Cely, a wealthy wool merchant who died in 1482.

The crypt, which can be visited still, dates from this period.

Upon returning to Norway, Olaf is known for bringing Christianity there; he was canonised after his death in 1030 and became the patron saint of Norway and known as its “Perpetual King”. Our church on Hart Street could well have been built on the site of the battle.

In 1658 a new churchyard gate was erected, decorated with a rather macabre row of skulls. The skulls were no doubt intended as a reminder of the need to be protected from evil, but they prompted Victorian author Charles Dickens to dub St Olave’s, ‘St Ghastly Grim’ in ‘The Uncommercial Traveller‘: “It is a small small churchyard, with a ferocious, strong, spiked iron gate, like a jail. This gate is ornamented with skulls and cross-bones, larger than the life, wrought in stone.”

In 1665 the Great Plague of London broke out around Drury Lane, and spread rapidly; 357 victims were buried in the churchyard. Their names were marked with a ‘p’ for ‘plague’ in the church register of burials. Mary Ramsay, popularly credited with bringing the plague to London, was buried in the churchyard on 24 July 1665.

One of the parishioners who survived the Plague was diarist Samuel Pepys, who worked in the Royal Naval offices on Seething Lane. Pepys and his wife worshipped in St Olave’s, and he recorded parish affairs in his diary for 14 years from 1660, often falling asleep in the sermons by the Reverend Daniel Mills!

Pepys had a gallery built, joined to the naval offices by a staircase, so he could attend services without getting caught in the rain. The gallery has been demolished, but a memorial marks the site of the stairway door, seen from the churchyard.

Pepys reacted to the devastating Great Fire in 1666, when he ordered nearby wooden buildings to be pulled down, to stop the fire from spreading so easily. The flames reached within 100 yards of the church, but a change of wind direction allied to Pepys’ foresight helped saved the church.

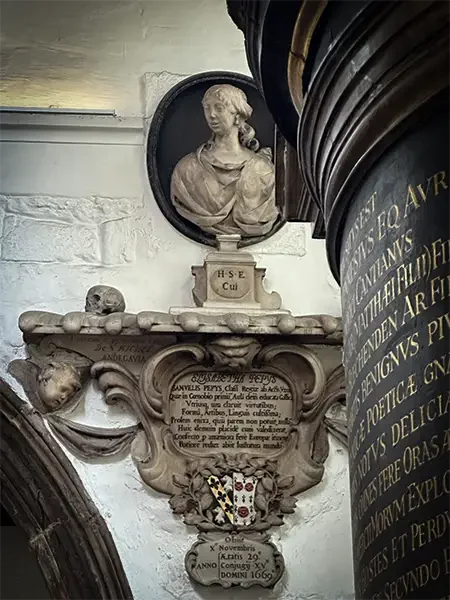

In 1669 his wife Elizabeth died of a fever and was buried in the church. Pepys had a marble bust of his wife sculpted and set on the north wall of the sanctuary, where he could see it during services.

As the President of the Royal Society, he was the publisher of Sir Isaac Newton’s Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica containing Newton’s Laws of Motion and theory of gravity.

Pepys himself died in 1703 and was buried in the nave beside his wife.

The Samuel Pepys Club hold an annual service and lecture in his honour, on or near the anniversary of his death on 26 May.

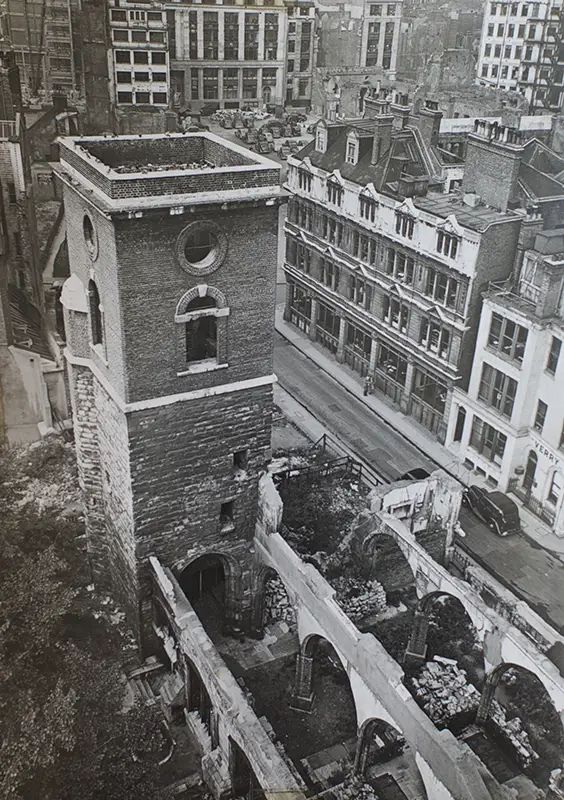

If you are interested in learning more about the history of St Olave’s Church, below is a link to an archive of a book called The Annals of St Olave Hart Street. It was written in 1894 by our rector of the time, Alfred Povah. It is a thorough history of the church and its contents. There are also some fascinating photographs showing how the church looked before it was bombed in 1941.

The church was heavily damaged during the Blitz of 1941, leaving just the arches and the tower.

During the war King Haakon VII of Norway sometimes worshipped at St Olave’s, after becoming an exile in England, unable to bow down to Hitler’s demands in occupied Norway. Following the destruction, St Olave’s was restored, under the inimitable vision and direction of the Rector, Augustus Powell-Miller.

The sympathetic restoration was by the architect Ernest Glanfield and rededicated in the presence of King Haakon VII of Norway in 1954. In 1951 King Haakon had laid the foundation stone, and a link remains with the Norwegian Church of St Olave in Rotherhithe.

Interior highlights include a colourful monument to Sir James Deane (d. 1608), and an ornate memorial to Pepys on the south wall. Another notable historic monument is that of Peter Turner, a wealthy physician who died in 1614; the historic bust went missing during the war and was rediscovered in an art auction in 2010 and rightfully returned to the church.

In the tower, there was formerly a memorial to Monkhouse Davison and Abraham Newman.

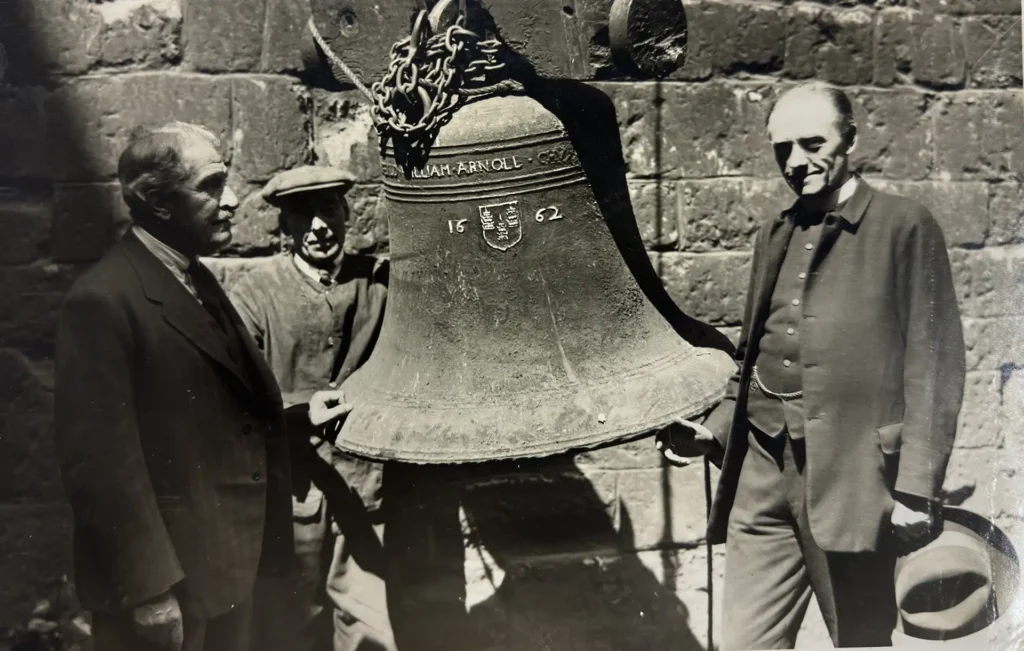

They were grocers with premises on Fenchurch Street who shipped a cargo of tea to Boston in 1773. The cargo was famously emptied into Boston harbour in a protest – The Boston Tea Party. There are also notable bells.

A number of histories have been written about St Olave’s, a history up to 1895 by the Reverend Alfred Povah, along with All Hallows Staining and St Katherine Coleman. The tower of All Hallows remains, on Mark Lane next to the Clothworkers’ Hall.

A history of St Olave 1895 to the present by Brian Grumbridge, published in 2020, is available for sale, as is a short pictorial history and guide called ‘Our Very Own Church’, available from the church office.

St. Olave 8 Hart Street, London, EC3R 7NB Registered Charity No:1130893

Phone: 020 7488 4318

Email: admin@saintolave.com

Sunday Morning Service

@11AM

Tuesday Afternoon Service

@12:30 PM

Monday: 10:30am to 5pm

Tuesday: 8:30am to 5pm

Wednesday: 8:30am to 5pm

Thursday: 8:30am to 5pm

Friday: 10:30am to 5pm

Saturday: Closed

Sunday: 10:50am to 1pm

© Copyright – OceanWP

By continuing to use this website, you consent to the use of cookies in accordance with our Cookie Policy.

Accept